There's a scene in the fourth season of Succession, an HBO TV show, where the protagonist--Logan Roy, tells his would-be heirs that they "are not serious people." It's a curious thing to say. What are serious people?

I suppose that in the context of a TV show like Succession, where the narrative is about an ageing billionaire business founder thinking about the future of the business he created...A serious person is an individual capable of building or stewarding something of meaningful significance. In his case, his business empire.

A secondary element, and within the context of that specific episode--the more important point; serious people are respected people. These are individuals who are well regarded because of what they have achieved on merit by being exceptional. Not only are they intentional--they are achievers. In the TV show, Logan's children are largely mediocre individuals who have not achieved anything in their own capacities. They largely owe their positions to his accomplishments, and lack their own. In the scene I referenced, he is reminding them that in the grander scheme of things, no one really respects them--and in truth neither does he. It's a poignant scene, and especially because they want him to treat them as business peers. Except of course they are not peers. Their magical thinking deludes them into having a false sense of self and importance. His comments are intended to deflate that delusion. To remind them that in fact he is the serious person to whom they owe everything.

What's the point of this reference to Succession?

Some months ago I wad discussing "the African situation" with a friend and fellow Afrophile. What I really mean is we were lamenting what we saw as a lack of economic progress relative to the resource potential of the continent. Especially in light of the progress achieved in other places in the world. My friend had an interesting thought. He asked a question. Do we as Africans value seriousness? Are we serious people? It was a great question. It's a big question. A question many people may even find offensive to ask.

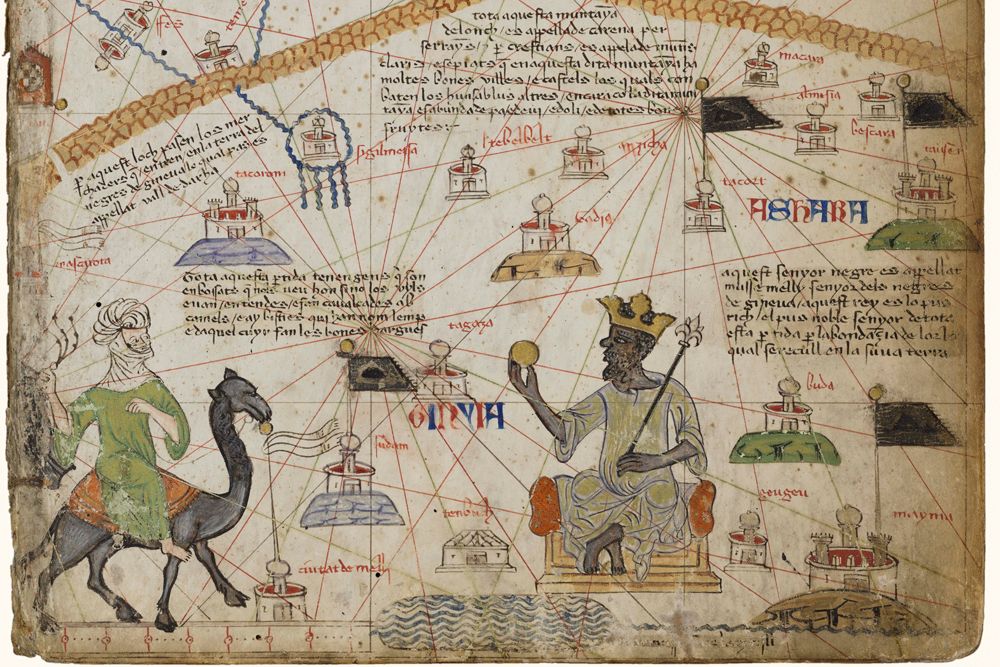

I have an evolving view on this. But in sum, I believe that African cultures traditionally were in fact serious and valued seriousness--in their own ways. One can not look at the Benin bronzes and not see seriousness in the detail of the sculptures. The same way one can not look at sculptures from Greece's classical period and likewise acknowledge the intentionality of the art. Across many of Africa's old cultures it is evident that exceptionalism was valued.

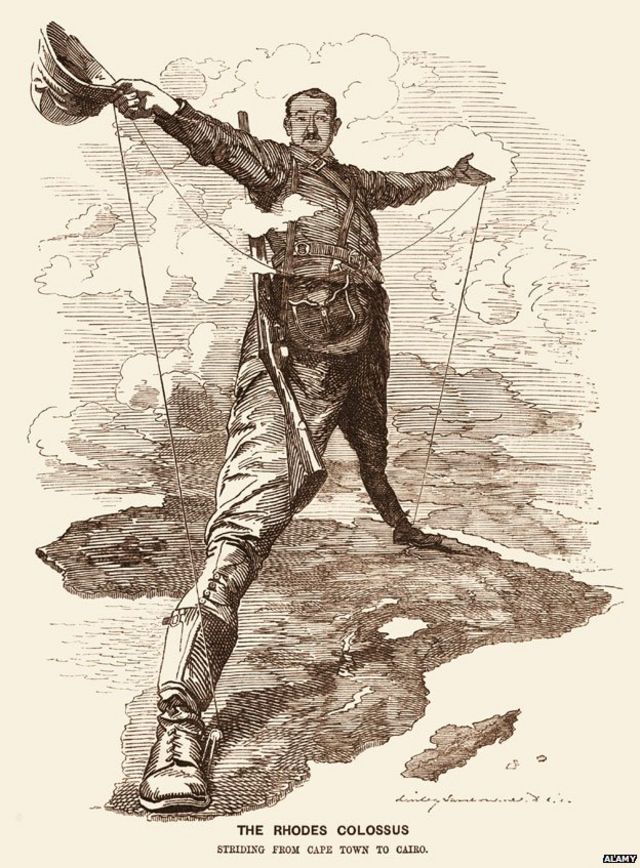

However, it's also evident that the humiliation of colonisation brought with it significant social change in Africa. Existing artisanal traditions were lost; traditional mining was not evolved by Africans to achieve scale in view of new markets being created. Africans, including those who knew how to mine or how to be blacksmiths were simply supplanted by colonising agents. The knowledge of these crafts was as such extinguished instead of updated. Would be apprentices became labourers.

The guiding ethos of colonisers was to bring "civilisation, commerce and Christianity" to Africa. The implication of this being the expectation of a blank-slate where previous "savage" traditions were to be forgotten and replaced with European civilisation, European commerce, and European Christianity. Colonial Africa had no space or regard for African civilisation, or African commerce; where it existed it was seen as backwards and only useful for keeping rural Africans in-check through the use of vanquished local chiefs as agents of colonial power.

Africa has been largely independent for the last 60 years. In that time, many countries have gone through several republic epochs. The country I live in, Zambia, is in its 4th republic. Ghana is also in its 4th republic. This isn't unique to Africa. Successful Asian countries like South Korea are also in their 4th republic, and arguments could be made that China is de-facto in a 3rd republic. The main difference between Asian stories like South Korea's and African ones such as Ghana or Zambia's is that South Korea is a wealthy polity whereas Ghana and Zambia remain poor countries.

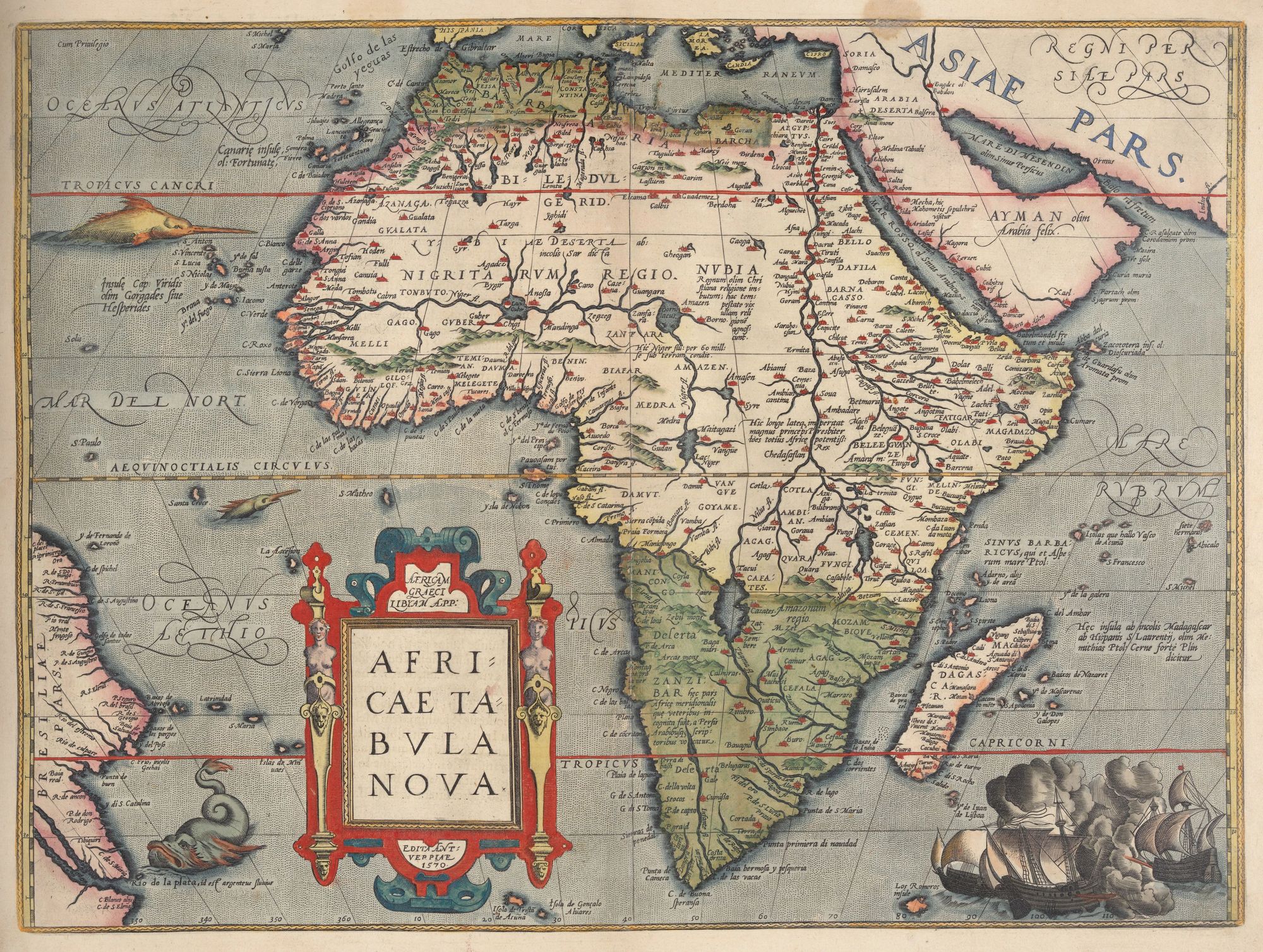

Africa's transition from colonial outpost to liberated continent was multilayered. Prior to Africa's rule by foreign colonisers, most polities were ruled by monarchs. What Europeans would call duchies or principalities were called "chiefdoms" in Africa, even when the geographic size of their possessions were larger than many European countries. These chiefdoms were subsumed into protectorates or colonies; with apex executive power typically held by a governor and their administration; with the chiefs deputised as managers of "native affairs" reporting into a "natives office." Whilst Apartheid South Africa came to symbolise racial segregation, the reality is that most of colonial Africa was racially segregated-- South Africa's segregation just ended approx 30 years later than everyone else's. Most of Colonial Africa was racially segregated. Life in colonies was split between the native world where people were either labourers or rural farmers, and the settler world where "formal institutions" held sway. As part of the civilising effort, schools were developed by colonising agents; often these were affiliated with Church denominations. Whilst there was certainly a noble element to this, in truth it was also a means of creating white collar native labourers to serve in the colonial administration and associated emergent businesses. This was in essence another way to erase the old and create something new.

Africa's emergent political leaders emerged out of the cadre of natives who were educated by the colonial powers and expected to be a new administrative class. Their academic training positioned them for work in the new cities being built by the colonial powers, so to the cities they moved. They worked as clerks, teachers, those who had university level training (either obtained abroad in Europe or locally at native only colleges) became professionals. Nelson Mandela for example was a lawyer, often representing natives. The proximity to settler life, and their exclusion from it created resentment among this group of emergent native elites. They were treated as second class citizens regardless of their intellect, or their achievements. Worse still this was being done in what they considered to be their own land.

Whilst this mistreatment was experienced by all, people in rural areas were far from the hubs of colonial power. In Zambia for example, the agricultural settlements, administrative towns and mining settlements were the true heart of the colonial enterprise. The far flung districts in rural areas were less engaged in the same sort of colonial interactions as these more urbanised nodes of power. Zambia, or Northern Rhodesia as it was called had a settler community that was only 2% of the colony's total population. This extremely small population held sway over the majority using fear of lethal force. Though in reality it was never truly possible to enforce it on the entire populace. This was a realisation that dawned on the emergent elite.

The native elite decided to challenge the colonisers for control of the states the colonisers had created. Over time these liberators achieved their goals and created new independent successor states. No referendums were held to enable their fellow natives to decide whether to revert to their prior polities; the various monarchies that previously existed. Instead they replaced the old elite with a new elite; whilst at the same time further reducing the formal power of customary leaders (the prior monarchs). The new elite kept the traditional (and informal) roles of the prior leadership structures (royal establishments) but sought to create modern states where formal institutions held sway. In this sense they were largely taking over the institutions created by the colonisers as opposed to creating something truly new. The innovations were largely an exercise in creating new cultural norms within these institutions such that they reflected rule by the indigenous people of the land. Even legal norms remained, common law countries continued to keep colonial laws on their books; eliminating what was no longer valid given the new context, and adding new laws that reflected the aspirations of the new elite and the people they represented.

Africa's liberation took form in the cold war. Whereas the US had been supportive of European powers shedding their imperial colonies. It was also nervous about the USSR's ambitions in the former colonial worlds in Asia and Africa. African countries were also nervous about colonial powers re-establishing their rule and that made them sympathetic to the USSR and China, who they saw as less racist. This resulted in Africa becoming a theatre of the cold war; and it was not without casualties. Patrice Lumumba was assassinated by agents supported by Belgium; Kwame Nkrumah was removed from office via a coup supported by Western intelligence agencies. These geo-political actions resulted in many African leaders becoming more hardline, and further aligning with the USSR and China, whilst nominally claiming to be non-aligned. The geo-political re-alignment encouraged dictatorships. Zaire which was aligned with the West was ruled by a dictator, much the same way Zambia was also ruled by a single party system with a paramount leader. The outcomes were similar because regardless of alignment both types of leaders thought they were (a) attempting to prevent sedition by way of coups (b) preventing regime change that may result in loss of native sovereignty. The consequence of this was that in many parts of the continent the merchant class had a diminished role in forming or shaping elite political/economic consensus. Instead consensus was directed to the elite by the paramount leaders. Those who disagreed could be labelled "anti-revolutionaries" and harassed by state power.

In my previous post I explored how building a political economy is in large part a process of building consensus among political, social, and economic elites.

When the consensus is anchored in decisions with significant economic outcomes--society thrives. When the consensus is anchored in decisions with significant negative economic outcomes, society suffers. Autocrats have the ability coerce elites and therefore can force a consensus whereas in liberal democracies consensus is achieved through debate, conviction building and demonstrating success. South Korea and North Korea are examples of countries where an identical groups of people led by autocrats pursued very different strategies for building their political economies and have thereby experienced very different outcomes. Ireland and Mauritius are liberal countries where consensus building has been achieved through debate, conviction building and demonstrated success.

In thinking about this and looking at Africa, where few countries have been able to build a successful political economy; I have to ask myself--why that is the case...

I suppose a good place to start exploring the answers to this would be defining what constitutes a successful political economy. A loose definition for a successful political economy is one where society maximally flourishes, where citizens believe justice is available to them, and the country has ability to defend its way of life. That last point, "its way of life" is key. Another way of thinking about that is that a successful political economy enables social flourishing, and that this success is a means of sustaining the sovereignty of the polity. In this sense common prosperity is an assurance of common security.

Going back to my chronicle on African statehood. At the end of the cold war, the USSR had collapsed. The West was triumphant, and the sponsor of many of Africa's socialist states was gone. Many of these states were themselves also economically vulnerable. After years of economic mismanagement under socialist autocrats, the citizenry sought prosperity. At a minimum for many of them, that involved a change of leadership; and like a wave, through the 90s many countries in Africa experienced regime change. This happened in part because political elites used this as an opportunity to safeguard themselves, secretly joining the new movements for change and thus assuring themselves of positions in the new orders. At the same time, using their existing positions to give their paramount leaders a false sense of security. The social consensus was for change, this was agreed on by both the proletariat and the elites; and so change came. However, as was the case under the old order, external geo-political forces often dictated local political manoeuvring. With the world in a uni-polar order, neoliberalism was paramount. With treasuries derelict, debts significantly high, formerly socialist countries opened up.

As these countries opened up, often under the auspices of structural adjustment programs; privatisations took effect, foreign companies begun to enter these new markets. This foreign direct investment was needed because hyper inflation had decimated pensions and savings. With little to no domestic capital left, and public companies largely bankrupt; restarting these economies required new infusions of capital. Foreign investors purchased state owned companies, and also established greenfield ventures. The political consensus was that people needed jobs, economies needed stability, and inflation had to be normalised. To achieve this the external neoliberal order had to take form domestically. In many countries in Africa, the immediate post-independence era had resulted in GDPs per capita declining, and this in part forced the change people sought--along with democracy. Itself a part of the changes brought on by a unipolar global situation. In this democratic dispensation, economic growth was required to enable political parties holding government to sustain their power at the ballot. In due time however, after 2 decades of being open. Many people across Africa begun to feel that the dividends of opening up disproportionately benefited foreign companies; along with the political elite. This resulted in a populist shift in the early 2010s, which itself resulted in significant public spending. Whilst this public spending was intended to redress perceptions of inequality, the largesse also had significant rent seeking elements.

Regarding rent seeking. In many ways the elite consensus across many countries has generally had this element to it. In some countries, Zambia for example, people will often point out that independence era leaders often lived modest lives once out of power. And this is true by middle class standards. However, relative to their rural peers; this is not the case. The average Zambian at independence and just after was either a poor rural farmer or a poor city worker. Political leaders and civil servants enjoyed a standard of life that was significantly better than the average citizen; and the same was true of locals who worked in State owned companies. Nominally there was nothing unethical about that, they had jobs to do and they were paid for these jobs in accordance to their rank. However, the disparity in lifestyles certainly turned normal jobs into a form of rent. People sought government jobs or work in government companies because it afforded them a better life. In a context where there were few private alternatives; holding on to these jobs was paramount. Losing the job, and with few private alternatives was a severe change in circumstances. This sort of situation reinforced political loyalties. Further, it also meant that those who had the power to give jobs, were in a position to distribute spoils/rents to loyalists. This situation remained through the 90s as democratically elected leaders overseeing economies in distress used jobs as a means of distributing rents. The two decades prior had set cultural precedence; and a paucity of private sector work made public sector work even more attractive.

As economies repaired themselves using foreign capital, and private sector jobs begun to be created; jobs ceased to be the primary lever of rent distribution. Populists begun to use public spending as a lever for rent distribution. This created wealth for what were often called politically aligned crony-capitalists. Sometimes this came with ostentatious displays of wealth; including burning of dollars on social media among other things. These public displays of wealth, and the high degrees of inflation and currency devaluation brought-on by excessive external public debt also resulted in political change, with governments being voted out of power and replaced with new governments that had a primary mandate to fix these economic challenges. This is largely the current situation countries in Africa are either experiencing, recently experienced or will shortly experience. This is broadly the state of affairs presently. New leaders replacing populists and faced with repairing the economic circumstances of their countries.

In recounting the above, one of the things that is clear is that the current modern state in Africa is largely in a sense a European institution that has been naturalised into its local context and is led by locals. The former power structures that were traditional remain largely nominal and informal. The intent of the colonising powers to bring their civilisations to Africa was largely achieved. Many African states have not replaced the colonial institutions with entirely new institutions that have taken the prior African institutions and adapted them for 21st century contexts. In a sense this has put African states in a situation where the use of institutions not created here leaves Africa constantly having to learn from others. This process is called "development." The end goal being African countries eventually become like those who formerly colonised them.

Since their struggles for sovereignty, Africa's elites have been engaged in what has largely been reactionary consensus building. An emerging elite sought to take power for themselves versus give it to former traditional leaders--and did this in reaction to colonial power. That same group of elites then designed their political economy to offset external geopolitical power; the lack of powerful commercial elites also gave political elites monopoly over consensus building; and turned government jobs into a resource to be distributed. Elites thereafter opened up their economies as a reaction to external geopolitical realities, whilst also attempting to fulfil the political mandates they had been given. However, in the absence of a powerful commercial class; public largesse eventually became a source of rents to distribute. Foreign businesses helped kickstart economies, but their lack of political allegiance allowed political operatives to see them as neutral actors. In contrast, domestic merchants were less neutral and any possible political alignment could result in harassment. This has created an odd dynamic where in many African countries, foreign investors have more incentives for scale. In contrast, South Korea opened up and also was very supportive of domestic businesses; providing state level support to enable their scale and global success.

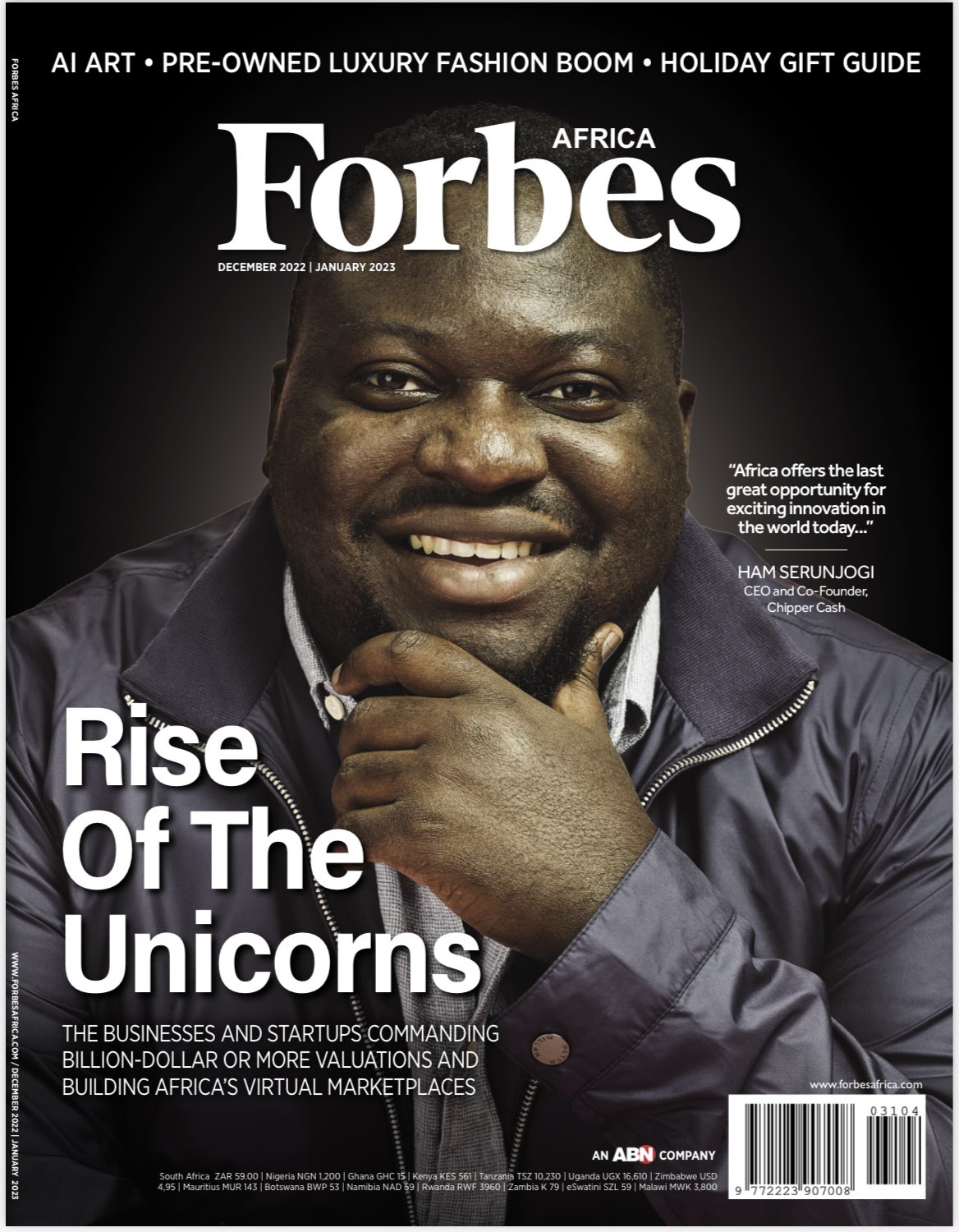

Elites in African countries have in the past largely failed to establish consensus on issues that might be able to establish sustained growth. They have been reactive and mostly focused on engineering outcomes that result in their attainment of power. In a sense there has in the past been a consensus, specifically engaging in rent distributions among themselves. Going back to the issue of seriousness. Africa is probably the least respected regions of the world. It is constantly seeking aid from the rest of the world. Its diaspora is faces prejudice. It is constantly being guided by others about how it should develop. For all of this Africa demands equal treatment. Colonialism has always been a feature of human civilisation; and whereas Africa is nominally equal and free, in substance it remains part of the European order. A place where resources are cheaply farmed and then exported elsewhere by foreign organisations. This isn't wrong in and of itself, free enterprise is good and has been a net positive. However excess requires concern. Africa is a resource economy, however it has few domestic resource billionaires. To a large extent the most productive elements of its economy are often not owned by domestic players; and Africans remain a source of labour for the most part. In contrast, Asian peers have been more balanced; enabling both foreign and domestic investment.

It is true that the policy mishaps of the past decimated domestic pensions and savings in many parts of the continent, reducing the value of the pools of money available for capital investment. South Africa is an exception in this regard precisely because its domestic pensions and savings pools are exceptionally large. However that has not sheltered it from the impact of policy making in its political economy. If the African state is to achieve broad and deep social flourishing, the sort that results in common prosperity and common security; elites in Africa will have to set a new consensus that puts the interests of African capital at par with foreign capital; they will have to set a new consensus that puts export growth as their priority--bravely supporting local entrepreneurs as well as requiring foreign investors to truly engage in knowledge transfers. More importantly perhaps, Africans broadly will have to recreate the African state in their own image; define success in their own terms, and build it from the ground up. It's interesting that the most successful African state in the world of movies, is an African technologically advanced nation with institutions of governance that entirely reflect its own character. To harness the potential of the future, African leaders may need to consider creating states that reflect the best of Africa's historic traditions, and adapt them for 21st century reality; borrowing from the rest of the world--but with intentionality versus succession.

In prior essays on culture (here and here) I explored why some organisations/institutions achieve vitality over extremely long horizons of time. One of the things that was apparent was that organisations that achieve success that endures over long time horizons are intentional, purposeful and focused on the quality of outcomes--in the extreme. They involve traditions that require their members to achieve extreme levels of professional expertise, and demand attention to detail regardless of this expertise. They demand thoughtfulness, and a deep respect for ensuring the reputation of their house remains intact. They think generationally. They consider the mistakes of the past, they are paradoxes; being extreme traditionalists and at the same time always adapting to their present reality. They create a strong sense of identity, and that helps make the people who work in these places proud of their association with those houses. These are qualities African traditions used to have, it is seen in their art--in their story telling, in their craftsmanship and legends.

This isn't to say everything about Africa's past was idyllic, it was not. Far from it. My point is that at least it was intentional, and to those who lived in those cultures it was serious. African states need to figure out how to inspire that level of pride in what they are today; and in lieu of the global reality--one where we are the least respected part of the world. That means we need to have a high regard for productivity and optimize around it. Our artists are already showing us the way. From Tokyo to Dubai to Los Angeles, you'll hear Afrobeats playing; and with people signing along to songs whose lyics they often don't know the meaning of. Excellence can be universally respected. We need to reach for it. Our entrepreneurs need support in building and selling products that are well regarded across the world. In doing so the elites who hold sway across the continent need to give space to African artists, African entrepreneurs and thinkers; to hold them up and support them instead of put them down. Failure to do so may lead us to a perpetual cycle of reacting to the rest of the world's geopolitical demands.

Africa needs to own its civilization again, from the ground-up. It needs to find its civilizational north star. Economic development isn't a north star, it's a means to an end. That end, the flourishing of African polity and its way of life needs to have a transcendent meaning that goes beyond economic output. What is transcendent needs to be paired with excellence. This isn't reaching for the insurmountable. The European renaissance was in part made possible by Europe reconnecting with its classical heritage, whilst adapting new technologies emerging through trade (including via the Silk road), and adapting them for their means at the time. There's no reason why Africa can't do the same--push forward, be excellent and be true to self. To strive to be taken seriously. In the long term it's the surest way for Africans to have true and meaningful security, lest the past repeat itself as often has been the case throughout history.